Get your ass to Mars: Armitage III Poly-Matrix

It’s Armitage III’s bad luck that it had to come out in ’95 – the same year Oshii Mamoru’s Ghost in the Shell movie did. GitS had a bigger budget and a bigger-shot director. Therefore it also had higher production values, more space for marketing, drew in a bigger audience. Armitage is always going to be compared to GitS on account of this confluence of circumstances, and it’s always going to come up a little short in comparison. Like its own eponymous character, the Armitage III OVA therefore always had to be the scrappy underdog fighting against the odds for survival in a cluttered market. But hey, isn’t that what cyberpunk is all about?

Armitage III is the story of a young female cyborg – Naomi Armitage – who is trying to fit as a cop on Mars, in a society that, if it knew who she was, wouldn’t want her and wouldn’t want anything to do with her. When a psychotic terrorist begins picking off high-profile Martians, Armitage is put on the case. The case starts hitting way too close to home for her, way too soon… especially since the terrorist strikes at the spaceport Sylibus is coming in on, almost as soon as he’s touched down. The victim, Kelly McCanon – the ‘last country singer in the universe’ – is revealed to have been a cyborg herself… and the killer’s MO shows that he is targeting illegally-constructed cyborgs like her: that are programmed look and act fully human, but are not. She’s also given a new partner for the investigation: Ross Sylibus, a transferred Chicago policeman with a bum leg who detests robots because one killed his last partner.

Armitage III started off, as alluded above, as a four-part OVA released in 1995, which was later edited and condensed into a full-length theatrical release in 1996 called Armitage III: Poly-Matrix, in its English-language release featuring the voice talent of Kiefer Sutherland as Sylibus and Elizabeth Berkley as Armitage. Even though the film is some thirty minutes shorter than the OVA series, the differences between the OVA and the film are largely cosmetic. Some of Ross Sylibus’s backstory is broken up into a series of flashbacks in the film. Some of the world-building and backstory, including D’Anclaude’s anti-religious and anti-robot rant during the fight scene in the church, are condensed or edited out. There is a different ending to the fight between the D’Anclaude second-series and Armitage in the government hospital. And the film has an original, more subdued and sombre ending than the OVA, although the plot beats are the same. The version I’ll be reviewing here is Poly-Matrix, since this version represents the parts of the story that Ochi Hiroyuki thought was most important to tell.

Even though Armitage III’s production values and artwork are clearly of a lower industrial grade than those of Oshii’s GitS, the world-building in Poly-Matrix is nothing shy of stunning. The design of the Martian city of Saint Lowell with its two-tiered skyscrapers, sunless sky and bubble of self-contained atmosphere is just plain fun. We get to see the function and dysfunction of Martian society through newcomer Sylibus’s eyes: incomplete terraforming, unemployment, failed attempts to establish an independent Martian national identity, anti-robot protests and bonfires.

The hard SFnal world-building is actually immersive enough that we actually get to see how the material conditions of Martian terraforming and settlement have shaped its politics. Minor spoilers ahead. the reason why robots had been so prevalent in Martian life is because they were first needed in the terraforming project to establish the conditions (atmosphere, liquid water, plant life) necessary for permanent settlement. These were (presumably) the ‘first-generation’ Martian robots. The ‘second-generation’ robots, mass-produced by corporations like Conception, are the ones that look human and work in service positions within human society. These ones are generally the focus of ire for the (human) Martian working class, who see them as a threat to their jobs.

Of the ‘third-generation’ robots we see, all but one of them are female, and apart from Armitage and Moore, all of them work in the creative sector: a country singer-songwriter, a novelist, a painter, a dancer, an actress. We learn that these cyborgs are meant to display the full range of human emotions and creative talent, and also are given the ability to get pregnant. They can procreate with humans, give birth and care for human offspring. They were manufactured as a response to Mars’s demographic inability to replace its own settler population without a steady influx of Earth immigrants like Sylibus. We even see the first attempts at a ‘fourth generation’ of Martian robots, or ALIVEs, which are meant to harmonise Mars’s nascent œcosystem with human flourishing, and are given bodies and consciousnesses which do not at all resemble human ones.

The politics of Mars and Earth are also shaped by these material conditions, which actually gives the film something of a Marxist feel – even though human workers are not regarded with any particular sympathy vis-à-vis their robotic counterparts. Martian society is still very much colonial in its mentality, while Earth’s visibly wealthier and more powerful united government has embraced a kind of feminism which ideologically opposes the existence of artificial reproduction. Much of the action occurs on account of these two very different worlds coming back into diplomatic contact with each other. End spoilers.

This keen and intricate attention to world-building is not surprising: Konaka Chiaki and Endô Akinori are the screenwriters behind Armitage III. Konaka’s later series like Serial Experiments Lain and Texhnolyze also showcase his talent for world-building, as well as for his literacy in classic SFnal and speculative literature including the Lovecraft mythos (Armitage’s name is a direct shout-out to The Dunwich Horror). And Endô Akinori, who also put pen to paper for Gunnm and Cyber City Oedo 808, is also clearly comfortable working with high-low distinctions in far-futuristic settings, and is clearly at the top of his game here.

As might be expected from a film like this, the action sequences and fights – mostly between Sylibus, Armitage and the assassin they’re investigating and chasing – are well-choreographed, detailed and animated. One particular sequence in the sewers, which involves a cleaner mech and which results in Sylibus losing most of the right side of his body, ends in a particularly satisfying feisty sign-off and one-liner from Armitage. The showdowns at the government hospital and outside the terraforming dome are also very well-done.

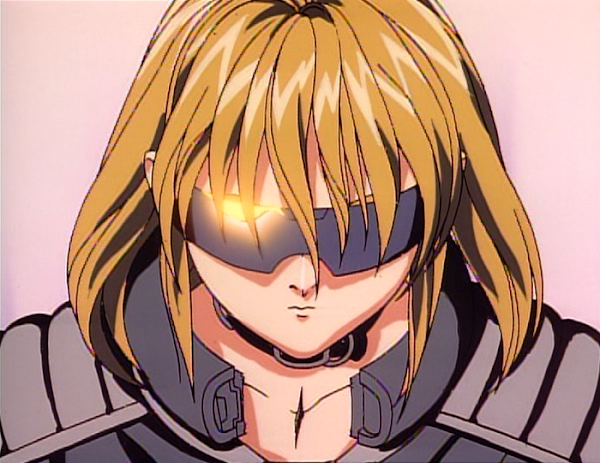

Unfortunately the artwork doesn’t quite match up consistently to these promises of the setup and storyline – the inkwork and shading are a bit flat; and even the background art during the actual action seems a little generic and claustrophobic given how much attention was spent on some of the establishing shots, set pieces of Saint Lovell and the surrounding Martian landscape, and exposition. Many pains were clearly taken over Naomi Armitage’s character design – a petite blonde ‘terror in hot pants’ and dominatrix gear complete with cuffs. She certainly has more of a personality than Oshii’s criminally-spayed version of Masamune Shirow’s Major Kusanagi, which is great to see. Armitage is good-looking, she kicks ass, she knows it, and she has motivations and an inner life of her own that allow us to sympathise with her readily, just as Sylibus learns to. Naomi Armitage also grows and matures significantly as a character as she learns more about her origins, purpose and capabilities, which is actually one of the major draws of the last half of the film.

Quite a bit of time was clearly spent on designing some of the other robotic designs, military equipment and vehicles. In comparison, many of the other character designs – including, unfortunately, Sylibus and the other Thirds – seem a little, well, generic.

The music, however, is excellent, although they redid a lot of the music in the transition from OVA to film. The title theme is a catchy dark techno number which perfectly suits the mood. The rest of the score is a nice balance of ambient, techno, acid rock and industrial with wistful little catches and hints of country-Western thrown in. This blend complements nicely both the action sequences and the exposition segments among the double-layered city with its massive screens, neon-drenched red light districts and frontier-settlement outlying regions.

There is also a typically-Japanese problem at play in Armitage III, from what I can tell: robots are generally treated with greater sympathy than humans. This is something that we can perhaps thank Tezuka Osamu and Atom for – indeed, you can notice some of the same dynamics at play in Metropolis, for example. Speaking in general terms, though: Japanese society embraces robotics with both arms, but still has some massive problems with entrenched discrimination and institutional racism against labourers from the Philippines and Korea, even ones whose families have been in Japan for generations.

In Armitage, you see marches and violent street protests and bonfires against robots which are deliberately made to take on nativist and nationalist tones, and I can’t help but wonder if Ochi and Konaka see the irony at work here. After all, the Thirds are meant to simulate humans genetically, somatically and emotionally – the only real differences between Armitage and Sylibus at the end, we are meant to see, are not philosophical or biological but instead political ones. (The OVA makes this even more explicit than the film, by tying up that loose end with a fake ID from Earth.) That is to say: the exploration of robotic dignity in Armitage III is not an SFnal question. Instead it’s one with allegorical meaning for how human workers are treated in our own day and age – particularly in the service industries and care professions. During the final montage, there is a sequence where a number of robotic workers in said industries are watching screens, showing Armitage and Sylibus defending themselves against an assault by the pro-Earth military forces. Given this montage I’d like to think that Ochi and Konaka would be sympathetic to this reading, but that’s nowhere near a given thing.

Anti-robot march in Saint Lowell in Armitage III (left),

Anti-robot march in Saint Lowell in Armitage III (left),Anti-immigrant worker and anti-Korean march in Shinjuku, 2014 (right)

But this is a minor gripe about a certain potential cultural blind spot. The very fact that I can point out parts of the SFnal setup like this, and relate them to real-world current-day problems, shows that Armitage III is more than holding its own and doing its job as a work of science fiction in terms of holding up a mirror to present reality. And the fact that the series doesn’t necessarily beat you over the head with these parallels isn’t an indictment of the writing or of the directing.

In practically every other aspect, Armitage III: Poly-Matrix shines. It’s gritty, it’s provocative, it’s entertaining, it’s captivating, it’s thoughtful. It maintains a decent level of dramatic suspense. In my humble opinion as a reviewer, the film does a little better job than the OVA of ‘showing, not telling’ key points of the plot, and bringing the series to a satisfactory conclusion. As I mentioned above, it’s a little rough around the edges, particularly in terms of the animation quality, artwork and some of the character designs. But for all its lack of polish, it’s still a worthy entry in the library of any lover of Japanese cyberpunk. In the immortal words of a certain former governor of California: ‘Get your ass to Mars.’

Comments

Post a Comment