The shallow self-importance of The Button

Vladimir Tarasov’s project which immediately followed The Return was the sketchy, mostly-silent short The Button. I have to say that this was the first of his works that I didn’t really like. The premise felt pretentious. The story was stretched thin even for a ten-minute short. The main characters were unlikeable. The musical choices were something of a mismatch, though I found it hilarious in an 80s camp kind of way. There’s still a wide degree of artistic talent to appreciate here, as in all his prior works, but it’s used to tell the bottom-line uninteresting story of a self-absorbed artist who gets jealous of his own fantasies.

There’s actually really not much more to tell about the story. The artist – with whom we’re supposed to sympathise because he doesn’t kill the fly buzzing around his studio – paints a self-portrait. A button falls off his shirt, and he paints it on the self-portrait – along with giving himself a fancy sports jacket, an expensive car, a country mansion, a medal of military merit. The portrait starts to come to life and starts demanding things, and also pulls the wings off the fly – so we know this guy’s no good. Then the artist’s girlfriend comes over and sees the painting, and the portrait successfully starts trying to seduce her. The artist then whitewashes the portrait, and the girlfriend storms off in a huff. The artist then paints a more realistic portrait of himself, which gets successfully shown at a gallery. The girlfriend shows up, having apparently forgiven him, and sews the button back on his shirt.

Unless The Button is a conscious satire of bohemian self-absorption, which is unfortunately not readily apparent, this short really doesn’t work too well. Like I said, all of the characters – not just the portrait – are silly and selfish, and none of them is particularly likeable. True, the artist does eventually decide to represent himself more realistically. Also true, his girlfriend does come back to him. But the artist’s motivation for repainting is his jealousy of his own shadow, and his girlfriend’s motivation is the artist’s success. These people are shallow, vain, materialistic. I’m not sure they are supposed to be this way in HG Wells’s original short story (which seems to have borrowed a bit as well from Gogol’s short story ‘The Nose’), but the animated adaptation doesn’t particularly do a lot of good service to them.

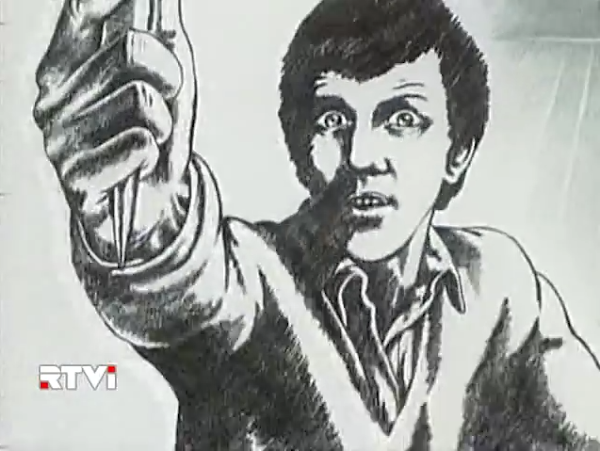

The art style is deliberately ‘sketchy’. Sometimes the artist himself – or the fly, or the eponymous button – are deliberately transparent to their backgrounds, like they were pencilled over. The artist with his ‘mop’ 80s hairstyle and buttoned cardigan resembles a bit the young Anton in Night Watch. The animation style to The Button makes it look itself like a painting in progress – pencil and charcoal, then watercolours and oils: the only colour in the whole piece is seen in the artist’s fantasy-portrait of himself. Æsthetically, this is an intriguing choice. There are some sequences where the animation, though certainly not the tone, reminds me of the brilliant – and much more soulful – British 1982 OVA The Snowman, based on a children’s picture-book by Raymond Briggs. But there’s nothing like the kind of emotional connexion or sweet wistfulness of that work, here in The Button.

The music is worth remarking on. There’s a lot of instrumental jazz, with a bit of scat vocals going on over it. The part where he’s painting his idealised portrait is suddenly accompanied by an upbeat 80s rock number. I suppose that particular choice was made to highlight the artist’s materialistic dreams of wealth and fame and prowess. But in context, the blunt musical shift has an effect that isn’t so much startling as it is unintentionally hilarious.

Anyway, I can’t really recommend The Button, except for hardcore devotees of Tarasov or of low-rent adaptations of HG Wells obscura. The only real thing to love about The Button is the unfinished visual art style. If Tarasov was aiming for a satirical angle – which, in fairness to him and given his other animated works, he may have been – he unfortunately kind of missed it with this one. The Button plays itself too seriously.

I mostly liked this one, actually. Like "Shooting Range", I don't think it's meant to be taken literally, but more as a philosophical/symbolic exploration of an idea/concept. In this case, what it's exploring is the negative side of creating a presentation of yourself that is "false". If you present a false image of yourself, the danger is that others, even somebody you care about, will come to like it more than the "real" you. So, better to try and "make it" as who you really are, not as a false image of yourself. Which doesn't mean that you shouldn't try to be your best self - that's what the titular "button" (which appears at the beginning and at the end) is all about; his girlfriend reminds him at the end that he can be himself and be successful in life, but should still make some effort to not be a slob.

ReplyDeleteThis idea about "truth in representation" (or mistrust of visual art in general) intersects with a lot of ideas you'll find in various religions. It also has a very old pedigree in Russian cultural discourse (it was one of the tenets of "socialist realism", of the battles against formalism, later becoming the Soviet Impressionism movement in painting, and existed in the pre-Soviet period as well, including in literature. In Soviet music, it was seen in mass movements such as the post-1950s backpackers' songs (туристские песни), wherein truth/authenticity was valued above any other artistic considerations).